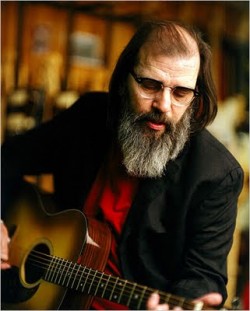

Steve Earle And The Ghost Of Hank Williams

Book Review: I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive

Book Review: I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive

Musician Steve Earle made a solo name for himself with Guitar Town andCopperhead Road after playing in legendary country and bluegrass bands as a young prodigy. He was nominated for a Grammy, his reputations soared, he added rock and roll to his range-until 1991, when Earle put out the aptly named live album, Shut Up and Die Like An Aviator. Shortly thereafter, he was dropped by his record label for long-standing drug problems, and landed in prison with a heavy sentence for possession of heroin. He completed rehab successfully, earned his parole in 1994, and has gone on since then to make several highly successful albums, guest star in the TV series The Wire, and write music for the New Orleans-based series Treme.

And now he has written a novel called I’ll Never Get out of This World Alive, set mostly in San Antonio, with a main character who is an aging doctor and a heroin addict. Doc’s specialty is quick but relatively safe and sterile backroom abortions, commonly performed on illegal immigrants. His license to practice long ago taken away, Doc takes in enough to make his daily pilgrimage to the parking lot where his longtime dealer works the streets. The book’s title is taken from the name of a Hank Williams song, which is appropriate, because whether or not you enjoy this novel may depend upon your reaction to Hank’s ghost hanging around the main character, begging for a drink and some attention. Things get even stranger when a young Mexican girl, Graciela, falls under the doctor’s care, and begins to exhibit signs of stigmata and the power to heal drug addicts. Rather than choosing to tell his tale straightforwardly, Earle is working more in the tradition of Latin American magical realism. This is no One Hundred Years of Solitude, but a lot hangs on belief, and the power of unseen forces to organize events in unforeseen ways.

Earle has a fun, quick touch with character description and the telling anecdote, explaining, for example, that local narcotic detective Hugo Ackerman “rarely hurried even when attempting to catch a fleeing offender. He had worked narcotics for over a decade, and in his experience neither the junkies nor the pushers were going far. He caught up with everybody eventually.”

Set in 1963, the book carries us through the Kennedy assassination and other cultural events as background. And we get a nice, deft description of what starts the doctor down the road toward smackdom: “Then in the first year of his residency he befriended a crazy old pathologist who worked the midnight shift in the county morgue, and it was he who introduced Doc to the miracle of morphine. From that very first shot it was as if he’d discovered the one vital ingredient that God had left out when He’d send Doc kicking and screaming into the cold, cruel world.”

I won’t say that Mr. Earle should give up his day job on the basis of this outing, but I do think that critics who have dismissed his efforts have overlooked some of what the author is attempting to say about addiction, and about recovery–that recovery involves all kinds of intangibles like faith, hope and charity, and that these attributes can present themselves in myriad disguises. (And a lot of critics got it: Michael Ondaatje wrote that this “subtle and dramatic book is the work of a brilliant songwriter who has moved from song to orchestral ballad with astonishing ease.”)

I think this book is, in fact, written very much with addicts in mind. The shade of Hank Williams doesn’t dog Doc everywhere just because Steve Earle is a huge fan. Hank Williams was also a vicious, go-to-hell alcoholic and drug addict who could not make the turnaround Steve Earle has made, and therefore could not even get out of his twenties alive, let alone this world. Earle has Doc stand in for him when it comes to lessons learned: “Doc was immediately sucked in by the big lie that all junkies want to believe in spite of daily evidence to the contrary, that this shot was going to be like that first shot all those years ago. He tied off, found the money vein in the back of his arm, well rested now because he had always reserved that one for the big shots, the teeth rattlers, and it stood at attention like a soldier on payday.”

I won’t give out any spoilers here, as the miraculous Graciela bleeds from her wounds and lays hands on dying addicts to save them. It’s the stuff of, well fiction-but fiction informed by the author’s firsthand voyage into heroin bondage. Steve Earle is living proof of the overarching theme of his book: redemption in its many guises.

Photo Credit: http://www.troubashow.com/