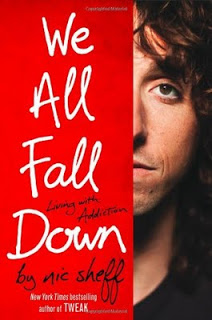

Falling Down And Getting Up: Nic Sheff’s New Addiction Book

Sheff jumps back on the carousel, lives to tell about it.

Sheff jumps back on the carousel, lives to tell about it.

What would it be like to have written a drug memoir and an autobiography before you turned 30? Would it seem like the end or the beginning? Are there any worlds left to conquer?

The last decade has brought us fleshed-out young examples by Augusten Burroughs, age 37 (Dry); Joshua Lyons, 35 (Pill Head); and Benoit Denizet-Lewis, 33 (America Anonymous). This more or less fits the pattern established by the doyenne of the genre, Elizabeth Wurtzel, who, at age 35, wrote the addiction memoir More, Now, Again. And now along comes Nic Sheff to put them all to shame, making geezers out of every one of them. Sheff wrote Tweak at 24, telling the world about addiction and how he’d conquered it. Well, as it turns out, not really. But for twenty-somethings, a week is like a year, so two years later, in actual time, comes We All Fall Down, in which we learn-if we didn’t learn it the first time-that the author is still learning about addiction, doesn’t have it figured, and isn’t really qualified to give out lessons to anybody just yet. Or perhaps I should wait for We All Stood Up Again two years from now before drawing any conclusions.

I know I am being a bit unfair to this well-intentioned young author. I blame it on the flood of weighty pronouncements found in the addiction memoirs that have flooded the market lately. God bless ‘em all, but Amazon, by listing Sheff’s book as “Young Adult,” probably gets it about right. You can’t go into these projects expecting great literature. Sheff’s text, perhaps in a deliberate appeal to younger readers, is peppered with whatevers, and clauses that begin with “like.” His favorite adjective, without question, is “super.” Too many one-sentence paragraphs give the book an irritatingly staccato effect at times.

But let’s get beyond that. There are good things here, and Sheff is certainly qualified to tell an addiction story: “We stayed locked in our apartment. I went into convulsions shooting cocaine. My arm swelled up with an abscess the size of a baseball. My body stopped producing stool, so I had to reach up inside with a gloved hand and….” And so forth.

There is a standard tension in addiction memoirs by young writers. The dictates of group therapy and 12-step treatment programs clash mightily with their innately sensitive bullshit detectors. It is hard-understandably-to buy into some of the more narrow-minded and coercive treatment programs they’ve been tossed into along the way. I was chilled to hear Sheff quoting substance abuse counselors threatening to commit him to lockdown psych wards, or blackmailing him into signing contracts about who he could or could not be friends with in the compound. For a free-spirited, open-minded young artist, the distinction between rehab and a Chinese re-education camp is pretty much lost entirely when personal freedoms are arbitrarily limited by lightly qualified drug counselors. One of the more compelling themes of the book is that rehab, as practiced in many treatment centers across the country, is something of a cuckoo’s nest joke. It is a mutual con, where everybody fools everybody in order to turn a profit, on the one hand, and discharge legal or parental obligations, on the other.“Infallible institutions,” as Sheff derides them, “that know, absolutely, the difference between right and wrong.”

So Sheff plays along, he shucks, he jives, he lies, and it’s hard not to sympathize with him as he summarizes one counselor’s admonitions: “We don’t allow any non-twelve-step-related reading material, and you won’t be able to play that guitar you brought with you-so we’ll go ahead and keep that locked in the office.” Much like prisoners who leave prison chomping at the bit to commit new and more lucrative crimes, these kids are coming out of misguided drug rehab centers with nothing but an urgent desire to wipe away the bad memories of mandatory treatment by getting wasted as soon as possible.

And yet, and yet… “Once I had some knowledge about alcoholism and addiction, it was impossible to go back to using all carefree and fun,” Sheff writes.“The meetings and the things people told me had pierced the armor of my fantasy world. Somewhere inside I knew the truth.”

Maybe there won’t be a need for a third memoir. The book has a provisionally happy ending. Sheff found the right doctor, got on the right medications after a diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder (comorbidity, the elephant in the rehab room), and, when last seen, is clean and optimistic.

Sheff does have an appealing, Holden Caulfield-type persona, and this Catcher in the Rye mentality perhaps excuses the litany of things in this world that are phony, fucked up, and lame to this endlessly hip kid. All carpets are faded, all motel rooms are dingy. Even his airline boarding pass is “stupid.” But the style sometimes works for him: “Thinking, man, even that cat’s got enough sense not to jump on a hot grill twice, no matter how good whatever’s left cooking on there might look to her.” Or the time when he realizes that, like any old alkie, it was time to “start switching up liquor stores. That goddamn woman makes me feel as guilty as hell. And, I mean, who is she to judge? Christ.” And he’s got some nice truisms to deliver: “The most fucked-up detoxes I’ve ever seen are the people coming off alcohol. It’s worse than heroin, worse than benzos, worse than anything. Alcohol can pickle your brain-leaving you helpless, like a child-infantilized-shitting in your pants-ranting madness-disoriented-angry-terrified… You don’t go out like Nic Cage in Leaving Las Vegas, with a gorgeous woman riding you till your heart stops.”

Photo Credit: http://www.goodreads.com/