Alcoholic Deception

Big Alcohol Wants a Piece of the Health Market

Big Alcohol Wants a Piece of the Health Market

For a long time now, snack food companies have been spending billions to convince shoppers that their fattening food offerings are fit and healthy nutrition alternatives. Big Alcohol, which has played around the edges of all this with “lifestyle” beer commercials, has been pushing into the health business more steadily of late, as opportunities for advertising shrink. The Marin Institute, which has got to be Big Alcohol’s least favorite advocacy group in the world, just released its new study: “Questionable Health Claims by Alcohol Companies: From Protein Vodka to Weight-Loss Beer.” The group documents the many ways in which alcoholic beverage makers are seeking to emulate food corporations in staking a misleading claim to words like “natural” and “organic.”

“The wine industry has been exaggerating wine’s health benefits for years. Now Big Alcohol is taking such messages to a whole new level,” said Marin Institute’s Research and Policy Director Michele Simon, one of the report’s authors. “Major alcohol companies are exploiting ineffective or non-existent regulatory oversight,” she added.

The Marin Institute breaks down Big Alcohol’s advertising assault into three areas of concern: adding nutrients, using the term “natural,” and using alcoholic beverages in fitness-themed promotional campaigns. It’s a free country, more or less, and there’s no point being a prude about these things. But a deeper look at alcohol advertising strategy can be enlightening. As the Marin Institute admits, alcohol’s advertising strategies “may seem relatively harmless.” but when it comes to promoting sales, the consequences are “potentially dangerous.” And overlapping regulatory agencies don’t make it any easier. Technically, the U.S. Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) is in charge of regulating alcoholic beverages, but the U.S. Federal Trade Commission has control over alcohol advertising, and determines whether it is unfair, false, or deceptive.

Here is a portion of the Marin Institute’s list of unsupported health claims:

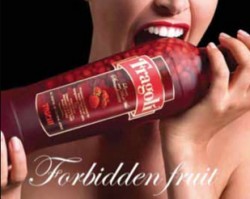

—Fortified vodkas. Fortified foods have been around forever, but it wasn’t until 2007 that the first fortified vodka hit the market. Lotus White, infused with added B vitamins, “could actually be good for you,” said the company’s CEO. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) prohibited Lotus from advertising the B vitamins on its packaging, so CEO Bob Bailey told the press that Lotus White provided drinkers with 100% of their daily recommended intake of B vitamins. “Alcohol is bad for you,” he told the press, according to the Marin Institute report. “Ours is just slightly less bad.” The report says that retailers in Los Angeles advertise Lotus as a “Vitamin B Enhanced Super Premium Vodka.” However, since alcohol is known to inhibit the absorption of nutrients like Vitamin B1 and B12, and folic acid, Dr. R. Curtis Ellison at the Boston University Medical School says that putting B12 in alcohol is “like putting vitamins in cigarettes.” Nonetheless, sales of Lotus vodka shot up 50% in 2009, says the Marin Institute, before the company went out of business last year. In November of 2009, along came Devotion, billed as the world first “protein-infused ultra premium” vodka. Sounds more like shampoo than a shot of vodka, but adding “protein” is now another marketing angle. The problem is that these approaches appear to fail the basic health rules of the regulatory agencies, to wit, that such claims must be “substantiated by medical research.” Try this one: Fragoli, introduced three years ago, a red liquid with a little red strawberry at the top of the bottle. “Forbidden Fruit,” has been one of the company taglines. And a company press release put it this way: “In a recent scientific study, researchers found that the addition of ethanol-the type of alcohol found in most spirits-boosts the antioxidant nutrients in strawberries and blackberries.” As the Marin Institute pointed out: “While the study they referenced did find that ethanol increased antioxidant levels in berries Fragoli implies that drinking cocktails is one way for people to get those antioxidants, which the study does not conclude.”

—All-natural spirits. Flavored vodkas have been with us for decades. But the competition is brutal. By 2008, there were at least 120 flavored vodka products on the market. The Marin Institute found that in that year, “three of the five top-selling vodka companies in the U.S. had ad campaigns with fruit and positioned their products as fresh or all-natural: Absolute (2nd), Skyy (4th), and Stoli (5th). Skyy was advising drinkers to “Go Natural,” with “100% real fruit and premium Skyy vodka,” as well as its line of “all-natural infusions.” Notably, the words “infusion” and “all-natural” remain undefined by the TTB. Similarly, Blue Ice vodka was among the 84 “organic” alcohol products that came on the market between January, 2008 and October, 2009. My particular favorite is Blue Ice Organic Wheat-certified organic by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), in a classic case of federal agencies in conflict.

—Fitness campaigns. Miller Lite, the “healthy” beer that started it all, launched in 1973, and ever since, commercial viewers have been subject to an endless collage of young people running, dancing, and diving into crystal streams. But it was not until the diet-conscious new century that sales of light beer exploded along with low carb diets. In 2004, Great Britain went after Michelob Ultra for its “lose the carbs, not the taste,” advertising, on the grounds that the campaign implied that beer drinking was part of a healthy lifestyle. No matter; Michelob went on to sponsor the UK Olympic teams in 2006 and 2008. By 2009, Michelob Ultra had no qualms about advertising itself as “a smart choice for adult consumers living an active lifestyle.” The Marin Institute has always been particularly rankled by the mainstay of beer advertising-sponsored sporting events. When Michelob signed a three-year deal with Lance Armstrong, the Marin Institute howled, because “the advertising campaign mixed images of Armstrong exercising and consuming beer while in the context of this activity,” another violation of the advertising rules concerning alcohol consumption and health.“Probably the most blatantly illegal advertisement came in early 2009,” says the Institute’s report, “when a new beer called MGD 64 (boasting just 64 calories) sponsored an online fitness program in association with Shape and Men’s Fitness magazines.” Again, the authors argue that if FTC and TTB standards don’t apply to alcohol-sponsored weight loss programs, then what DO they cover?

If you put it all together, “such marketing represents a significant failure in the regulatory oversight of alcohol advertising.” Small wonder, since regulatory oversight is split across two or three federal agencies, 50 state beverage control agencies, and state attorneys general. Plenty of regulating to go around, if it was more sensibly deployed. But if it were, protein vodka would probably not be on the market. The Marin Institute’s modest proposal is to transfer jurisdiction over the regulation of alcohol advertising practices to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), to which Congress recently granted greater powers of regulation for cigarette products. Once again, the institutional confusion and inertia caused by the artificial distinction between “legal” and “illegal” drugs is hampering efforts to effectively regulate the sale of this addictive drug.

Graphics Credit: http://www.marininstitute.org/site/